This is the story of how Dattner Group’s flagship women’s leadership program – known as Compass – gave birth to a global initiative for women with a STEMM background, leading for the greater good.

Homeward Bound is a global initiative for elevating the visibility of women with a science background, founded and literally ‘dreamt up’ by Dattner Group CEO Fabian Dattner.

It was conceived in October 2014, and, as of November 2022, has involved over 700 women with a science background from 48 nations representing 36 sciences in the 12-month program. The strategy states that by 2036, 10,000 women will have participated in the program and been given the skill and will to lead with impact and influence for the greater good

Approximately 1.3 billion people have heard of the program via comprehensive world-wide media, including video documentaries, podcasts television interviews, along with over 1,000 speeches that have been given by Homeward Bound women.

So, how did this come about, and how did it get so big?

1. HOW TO GET A PIONEERING IDEA OFF THE GROUND AND WORKING

Intuitive insight is an unconscious expression of expertise – ignore it at your peril

“Intuition is the ability to understand immediately without conscious reasoning and is sometimes explained as a ‘gut feeling’ about the rightness or wrongness of a person, place, situation, temporal episode or object. In contrast, insight is the capacity to gain accurate and a deep understanding of a problem and it is often associated with movement beyond existing paradigms.”

In the dream I saw we were in Antarctica, I saw the women, I saw the banner Homeward Bound, I saw over my shoulder a film crew, who I knew were making a film that interrogated the narrative of leadership. I knew we were helping the women to be more resilient, to manage being vulnerable without fear of being judged and to be able to see others more clearly – and so have greater choices about how to affect change with people. I knew we were focussing on women’s connection to the planet as home. I knew we were giving them best available science as it informs what is happening to our planet.

The program I knew we were delivering in the dream was an extension of all that we were achieving with the Compass leadership program we’d been delivering at Dattner Group for almost ten years – one that focusses on helping women clarify their pitch to the world, understanding that visibility needs to be purposeful, and in this instance, ensuring women can represent their science in a way that is understandable to non scientists.

What fed this intuitive insight?

I had worked for 30 years as both a social entrepreneur and leadership expert, working extensively with women, and passionate about our earth. I had founded and led several organisations and was running a leadership program for women only (Compass) for the Australian Antarctica Division (AAD). It seemed, by luck, all these elements would merge because of one singular interaction with that group.

The women participating were deeply experienced scientists. Eating lunch together one day, I listened as they shared stories about Antarctica. These stories were mesmerizing. But there was a moment when joy, vision and inspiration slid into frustration, then anger, then grief.

Why? Because these brilliant women felt they were routinely passed over for promotion in favour of less credentialled and less experienced men. These women were experts, many were advisors at global conferences or had worked on bilateral agreements on the management of Antarctica and were part of international collaborations addressing climate change and its consequences. They could see what was not working in the narrative of leadership and for a brief moment, under a stairwell in an unmarked building, were able to express their hurt and a sense of deep frustration.

- That night, I had the dream.

Advice

True vision is not something bestowed upon you by a munificent, magical being. It is the expression of expertise – as an artist, a physician, a technologist, a mother, a gardener, or, indeed, a CEO.

Expertise grows over time; it is accretive, layered. Part of the expert’s brain is making use of these expertise to successfully execute an outcome.

A big part of the expert’s brain is tracking for what we don’t know – the gaps, the problem to be solved. Vision emerges in the gaps.

If you find yourself unable to see the gaps, or, having seen them you are not generating ideas and possible solutions, this could mean that you are not feeding your brain enough food (which includes what you read, eat, listen to, watch and, of course, the many people you talk to). Input equals output.

We all have the same brain structures. This is important to remember. There is no such thing as ‘I am not a writer’ or ‘I am not creative’ or ‘I’m a doer not a visionary’. What is true is that some people have underdeveloped linear thinking and some underdeveloped lateral, or intuitive thinking. The part of your brain that is actively helping the most day to day is the part of your brain that gets the most exercise.

Both linear and lateral thinking is needed. What’s critical is to feed and foster the appetite for learning and discovery. If the CEO or top executive or expedition leader is not always thinking about and feeding their knowledge of future pathways, then who is?

2. POWER OF THE FIRST FOLLOWER – YOU CAN’T DO IT ALONE

On the morning of the dream, I had a gut feeling it was possible (that’s intuition). It could work, it made sense. It drew on all the threads of my own ‘expertise’ while also putting the execution into a context about which I knew nothing.

Having mentioned the dream to my husband, who thought it sounded like fun but was otherwise more interested in making the coffee, and subsequently my then business partner who laughed and said ‘over my dead body’ (though having more knowledge of leadership than many people I know, his engagement with women and the state of our world was relatively thin), I rang Dr Jess Melbourne Thomas.

Jess had done one of our Compass programs six months prior, and we’d just clicked. Jess is clever, a can-do person, very quick pattern connector, savvy about influencing and intellectually astute. She knows women in science, and she understood how much support women in STEMM needed to lead and to be visible. Following her participation in Compass, she had also been the instigator of the program taking place under the auspice of AAD.

Jess understood what was possible. She was the perfect first follower.

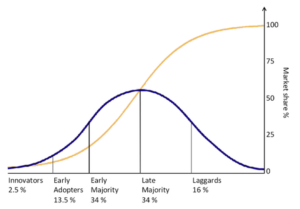

When others have skirted round the idea because it’s too risky, too ‘out there’, the first follower makes the ‘crazy’ plausible. The 2.5% of us who are innovators have a higher propensity for risk and a lot of the time can afford to fail. They do not, however, influence the majority to follow. The first follower does two things: they get in there with the innovator, become part of the idea and then they help early adopters join in. They are not averse to risk but they are not the ones to necessarily generate the ideas that others might think are harebrained. Innovators are those who create something or are the first to adopt an idea, product or service. They are willing to pay what it takes (money, time and energy). Early adopters, however, are more likely to think practically and to communicate an idea that someone else is proposing in a way that the early majority understand and feel comfortable with.

When I explained the idea to Jess early the next day on the phone, she loved it. ‘Why don’t you write it down and I will see who I can test it on.’

I cancelled an appointment and spent the next two hours scoping Homeward Bound – its purpose, audience, goal, key message, who would be involved, what we would focus on, a wish-list of global patrons, why Antarctica, why women, why women in STEMM. When I look back at this document, compared to where we are today, it is a kindergarten drawing. However, I did my part and then Jess did hers.

It quickly escalated up the ranks in AAD until then Chief Scientist, Nick Gales (who also loved and knew Compass) gave us the executive confirmation that told us it was worth getting behind. He couldn’t provide funding but crucially, he was an expert, a senior leader and an Antarctic Scientist. His validation gave us courage, and a small but growing coterie of women the mettle to bring in the early adopters. The early adopters became co-founders. None of us could have done this on our own. Together, however, it was a very different story.

Advice

- Understand the body of expertise that is informing your idea

- Invest time to mull over the vision you have

- Choose someone to talk to who shares your knowledge, passion, idea (their response rests on the same platform as your vision). Let them ‘catch’ the idea and make it their own)

- Bring them into the vision and give them freedom to engage with others

- Listen carefully to the feedback

- Refine your idea, let it evolve with added expertise and wisdom

- Identify your early adopters; they are both expert and doer

3. BUILDING THE NUCLEUS – CHOOSE YOUR TEAM WISELY

Within a month of the dream, my original paper had escalated up the ranks of the AAD. On the way up Jess had invited two women to give feedback: Dr Justine Shaw and Dr Mary Anne Lea. Both these women were early adopters.

They were brave, capable and intelligent. Most important of all, they had bodies of expertise that I did not have. Yet, and this is crucial, they shared the same values and vision. The attributes that would enable collaboration from such different contexts were rock solid. They had both done Compass and they both believed deeply that women leading in our world, with a STEMM background, mattered.

I think they would say they were both excited by the idea, but they would also say that the way I thought made them a little anxious. I clearly remember our first face to face meeting, outside AAD’s offices in Kingston, south of Hobart, Tasmania. We sat on a bench seat and for an hour or two and talked about the idea. What were our gut feels? How did we think the targeted audience would respond or what the content should be?

How could we access networks, including Women In Polar Science (they’d recently launched a Facebook network for this group).

We talked about ships, where we could depart from, what was required in a trip to Antarctica all the way through to how to manage sea sickness. We talked about influencers (in Antarctic science and business) who might help get the idea off the ground. We talked about our audience and how we could test whether they liked the idea.

Ami Summers was also in this early group. Ami was a member of the Dattner Group at the time and was responsible for managing Compass in Australia. She is a beautiful-in-spirit, smart woman with a calm kindness that makes everything seem possible.

As the conversation became slower, and the ideas stopped flowing, there was a moment when we looked at each other and said, ‘are we doing this?’.

The answer was a unanimous yes. So, we divvied up the tasks according to our skills, set a time frame to get agreed tasks done, and agreed when we’d meet up again.

Advice

As a senior leader, an ideas person, an entrepreneur or CEO, the team you have matters hugely.

Choose people who are evidently values-aligned and can take ownership of the idea in their own way. Don’t settle for talent over aligned purpose and values. Talent is great, but not half as valuable as genuinely aligned determination. If people really want something to succeed, and they belong to a purpose/values aligned team, your chances at success skyrocket. If those individuals are self-aware (and open to giving and receiving feedback without being defensive), miracles can become everyday affairs.

Note: Many executive teams underperform because CEOs are poor at setting expectations around aligned behaviour and a shared ‘why’ for what you do. Achievement is sub-optimal because there is a greater focus on the how of what they do rather than the why. The wrong people on the team, lack of clarity, poor decision making, inadequate skills at engagement are common.

4. WHITE WATER RAFTING – WHEN THERE AREN’T ANY EXPECTATIONS TO MANAGE, BECAUSE THERE’S NO PRECEDENCE FOR WHAT YOU’RE DOING

At this point in the Homeward Bound narrative, life gets exciting and slightly unbelievable.

The team divided as follows:

Justine and Jess started to look at getting Greg Mortimer involved as adviser and expedition leader (80 voyages to Antarctica under his belt), approaching senior leaders in Antarctic science to advise on and endorse what we were doing, and finding out how networks could be activated far and wide to support a test of our targeted audience.

Ami focused on best approaches for soliciting Expressions of Interest, and how we would go to market.

I focused on our networks, getting good business advise and persuading my husband that the idea would work, including that it was worth underwriting (i.e. using our home as security). I reached out to heroes of mine to ask if they would endorse the project. People like Sylvia Earle, Jane Goodall and Bob Kaplan amongst many others. All of them said yes, we will help.

At the time, I had also done a handshake deal with Greer Simpkin to make the film I had seen in my dream. Greer is now Managing Director of Bunya Productions, following many years working in editorial and production roles in broadcasting. Serendipitously Greer had been with ABC when we first met (again in Compass) and wasn’t happy. The 2015 handshake deal was later cemented with David Jowsey a celebrated Australian producer in his own right, and after two pitches (2015 and successfully in 2016) to Good Pitch Australia, the film team (Greer and Director Ili Bare) did a successful pitch. As a result, the project was fully funded.

While all this activity was occurring, the core team were growing as the idea gained momentum. We were joined by Kit Jackson (a strategist and close associate of Bob Kaplan), and Julia May and Sarah Anderson. Julia had taken over Ami’s job with Compass and she and Sarah had long felt that the specific issue of visibility was crucial in advancing women’s leadership. As a result, a new stream was added into our thinking on content for Homeward Bound.

Marshall Cowley, a long-term member of staff at Dattner Group, and the only man to sit at the center of this women’s initiative, joined as design architect, coach and facilitator and Michelle Crouch[6] Dattner Group’s operations manager, took over operations and finance of Homeward Bound.

We also commissioned a PR Agency to take the message of what we were all doing to a very eager public. This was to become a signature feature of Homeward Bound – creating a global media platform for all the women to stand on.

We gave ourselves six months to find the women who we hoped would join us. Approximately six weeks after the dream we went public with the expression of interest. In four weeks we had 180 applications. We had to close the EOI invitation because we were now confronted with the complexity of choosing 40 from 180.

By January 2016, the 40 were selected and we began the six-month journey of approaching countless bureaucrats in Tasmania and in Canberra. We spoke to many Antarctic specialists all of whom (with a couple of exceptions) were men. Everyone loved what we were planning and, in true Yes Minister style, nodded, agreed and passed us on to someone else.

There came a point in mid-2016 where we knew it would not be possible to leave from Hobart. It would have lent the project gravitas from a science perspective (Hobart is one of the key gateways to Antarctica for global Antarctic science) but the cost was prohibitive. We knew we could raise half the funds we needed from the participants themselves, but it just wasn’t enough to take a ship in our own right.

And so we made the decision to leave from Ushuaia in Argentina, a choice that led to a unique funding model: if we increase the size of the ship (taking 80 women), and if everyone pitches in a sum of money it would mean that we were 100% independent of any oversight body. All the materials and faculty would donate their time.

It was at this point in time we knew this trip would happen.

What we didn’t fully realise was that we weren’t just taking one trip to Antarctica, helping one group of women, we were unleashing a global initiative.

Working with a team of experts, in a fast moving, volatile, uncertain space, where there are no prescribed processes or rules is an utterly wonderful, inspiring, magical space. We selected participants sitting together in my living room, based on how we felt about what we read and saw. We worked on design, with Greg Mortimer muttering in the background ‘that’s a lot to do while you are in Antarctica’. We went to a second round of EOIs and again got inundated, which enabled us to secure a ship in our own right. We gave excited updates to our audience who tolerated that ambiguity with grace, humour and curiosity. We arranged sponsorship deals with big brands such as Kathmandu and we hurtled to departure day with sparkles in our eyes. We had pulled it off.

Advice

The excitement of the ‘first’ of anything is not to be underestimated. It is also not to be overestimated.

When you are trying to build a prototype, despite the expertise of the team, failure has to be anticipated. We did not plan for that. Rapid learning should be prepared for post launch. We didn’t do that. How the dream matches the reality should be measured (and a contingency plan prepared). We didn’t do that.

Could I have anticipated this as a leader? Not then, but I can now. Did I learn a lot as a leader? Yes. Could I have learnt it by listening to someone who had done it before? Yes.

So, the advice is simple

- Go for the best mentor you can find; the worst that will happen is they will say no. Find someone else. Keep going until you have trusted advisors supporting you.

- Failure is part of learning. If you aren’t failing, you aren’t learning. Plan for it, anticipate it, review for it AND it hurts – twice as painful as success is rewarding.

Great initiatives, acts of courage, changing paradigms is not for the faint hearted and neither is leadership.

5. ROAD OF TRIALS – CROSSING THE THRESHOLD, TESTS, ALLIES AND ENEMIES

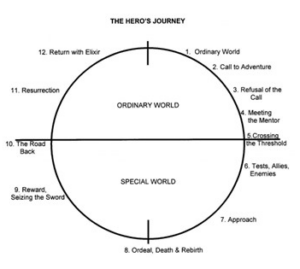

I have been a fan of Joseph Campbell for a very long time. Campbell described theories, most notably through his work The Hero with a Thousand Faces whereby the archetypal hero, through a series of steps and stages, departs from the ‘ordinary world’ in response to a ‘call to adventure’.

This conceit emerges in hundreds of modern day examples – from Superman and Wonder Woman to Neo, Keanu Reeves’ famous character in The Matrix.

It is, in essence, the story of an ordinary person who, in a variety of ways is called to an adventure outside their normal world. The Hero might refuse to respond to the call, but the truth is it is an irresistible gravitational pull towards something that can be done. Most heroes meet a mentor. For me it was the team of people who came together in 2015/16 who ultimately mentored each other. As time passed, this team grew and came to include a very brilliant quorum of our first cohort.

We arrived in Ushuaia (the faculty and participants) with star dust in our eyes and a deep sense of disbelief that we had done it, pulled off the dream, made it to the end of the earth and were soon to embark on a journey to Antarctica together with 80 women with a STEMM background (largest expedition of women ever).

Behind the scenes, lots of small things had gone wrong, including our film equipment and gifts for the women being held up in Buenos Aires in the hands of eager customs officials keen to see what additional fees could be demanded from us. But I remember very clearly, walking down the stairs in the hotel to the gathering area where a great cacophony of 80 women excitedly getting to know each other awaited, a camera crew following behind me, and thinking, this is one of the greatest moments of my life.

We greeted the women like friends and family. The faculty were ecstatic, the participants were energised and buzzing, the location was extraordinary, and we were off to dinner together to launch the program.

What could possibly go wrong!

The scenery was spectacular – snow-capped Andes surrounded us, the Beagle Channel was twinkling in the late dusk of a summer’s night. We arrived at dinner, where everything was going perfectly until…

We tried the first of our brilliant ideas (often mine, not thought through sufficiently in consideration of our audience). Having shown our very moving promotional video, ‘Mother Nature Needs Her Daughters’ we invited our audience to partner up with one other woman in the room and film a 30 second grab on what they would say to their own mother if she was ill (as our Mother Earth is).

A series of things happened at this juncture (some comedic and some prescient). Firstly, we crashed the questionable Wi-Fi in the hotel (something that a 15-year-old could have predicted in such a remote location) and secondly, we upset a number of women for whom this particular exercise was, in hindsight, potentially fraught.

While we overcame this quickly (the pull of Antarctica was mighty), it heralded a naivety (certainly on my part) that only the trial by fire articulated by Campbell in the Hero’s Journey could have predicted. This was not to be the only mistake we would make, and it was certainly not the hardest to fix.

Advice

- Matching reality and vision take time. There is no one to blame at times like this, just a journey to go on and a fire to walk through. Hold your head up, listen to the feedback and have a fierce enthusiasm for learning. Also, accept that sometimes a stiff whisky is entirely acceptable.

- CEOs are not infallible and setting themselves apart from their audience is fraught. A leader who can’t accept feedback without getting defensive is someone who will not build trust, and trust is the bedrock on which we stand when we have to have difficult conversations.

- Difficult conversations enable us to resolve conflict and build commitment. Commitment aligns people to shared goals and once we’re aligned, we can hold people to account. Surprise surprise, results flow.

The truth is, a lot of executives get anxiety about making mistakes. When they do, they hide them or they blame. This, far more than the mistake itself, undermines trust and commitment. I recognise that sometimes feedback is tough, unfair, rough, not what you expect, doesn’t reflect what you value, reflects something you’ve done or said that wasn’t what you meant. I know. I do. Really!

Even so, the advice holds true – STAY OPEN TO FEEDBACK. Ultimately, it’s a gift.

6. ANTARCTICA, THE FACULTY, OUR CONTENT AND A FEW TWITCHY DISRUPTORS

We left for Ushuaia the night after the welcome dinner. It is hard to explain the overwhelming sense of excitement, no small amount of adrenalin, thinly veiled fear (would we get seasick on the famous Drake Passage) and the palpable anticipation of finally, after two years of work and anticipation, getting to Antarctica.

The faculty were a strategically opportunistic collection of experts: Jus and MA leading the science stream, and the founders of our now famous ‘Symposium at Sea’ (where every participant has 3 minutes to pitch who she is and what she does/values to the full group), Marshall Cowley and myself leading the leadership stream, Julia May leading visibility, Sonqqiao Yao on logistics and communications, Kit Jackson leading strategy and Greg Mortimer as legal expedition leader.

Each of these people had been involved from very early on in the evolution of Homeward Bound – hours and hours in teams, and then many weekends at my home juggling segments. Jess had formally withdrawn to focus on her family and career early in 2016. The faculty on the first voyage had worked tirelessly since to identify and agree on the content, wrap their heads around how to design 21 days of programming in two hour slots to be delivered in completely unfamiliar environment.

We had met monthly online with the community and were all managing various parts of program logistics. We had no money and only a 0.3 FTE paid administration role. It was the purpose (women leading for the greater good) and visionary goal (1,000 women leading with a STEMM background by 2026) and the strategy of Homeward Bound[1] that guided all our choices. All of us deeply believed in the ‘why’ for what we were doing, and shared the same values – collaboration, inclusiveness, legacy mindset and trust.

It was a huge effort, difficult to convey in words. Some of the detail of what happened can be observed in the film that was released, The Leadership.

What is relevant here is that the experience was epic for all (Antarctica IS epic). For some, the journey failed to meet expectations. Of the 76 scientists on board, four struggled with the approach, the environment, and my style. This small group started to agitate and, as is the way with scientists, the causes of their agitation were given fair airplay. Issues of one or two became concerns for many, faculty included. As time progressed, we did our best to learn and adapt.

We finished the journey with a 24-hour process, run by participants on the ship, to capture feedback. This was carefully recorded, and a group of participants volunteered to type up the results, pattern them, send back to all participants for final review and then, once finalised, present to faculty.

At the end of the voyage, we had our final night in Ushuaia where we had genuine recognition that we had done something miraculous together. There were definitely learnings, but it was considered a success for such an epic undertaking.

What happened then, in the first three months post our return, went on to define Homeward Bound, change my sense of self as a CEO and social entrepreneur, be the source of a lot of anxiety and then, as we executed the lessons for Homeward Bound 2, become a source of relief, exhilaration and pride.

About three months after our return, we were presented a 13-page document which tabled the participants recommendations for improving what we had done. I remember receiving this at home with the faculty, presented by a team of alumni we had come to respect and love in equal measure.

Hard as it was, at times, to hear, we accepted the feedback almost in its entirety. There were times when I felt that I was the wrong person to lead the project, that I wasn’t capable for the seemingly immense task ahead – that of incorporating all the changes, both personal and practical. But I knew it was about taking one step at a time. Together with the amazing people on the Homeward Bound team, I was enough and I had enough to do the job needed.

This process of gathering feedback, developing awareness, sitting in reflection and then refinement went on to shape Homeward Bound 2 into the well documented success it became, and to pave the way for what would become a living, breathing reality in the world.

Advice

- When people have something to say about you, about what you are doing, about your faults or mistakes, it does not matter what you intended, or how skilled you are or how much you know. If you don’t listen, then rumblings grow, or people disconnect.

- Don’t lose sight of what you are trying to achieve. If you are stretching the boundaries, expect the challenge. If you have all the answers or maintain that you always knew what you are doing, you may be at risk of complacency.

- It is the CEO’s job to guide people through unchartered waters, as much as it is to ensure good systems and mitigate risk. The grander the vision (and Homeward Bound is a grand vision), then up go the risks and with that, sometimes mistakes.

- Listen carefully to feedback. Recognise the value of a disruptive minority. Put on your grownup pants and collaborate with respected others to stabilise the vision. Take note that visionary processes often lack good systems, so post a pilot of a visionary process, system changes are inevitable.

- To sustain energy for a big change, you need almost a religious commitment to the greater purposes, to your stakeholders, to your collaborators and to the outcome you are intentionally pursuing. If you don’t have this, the hurdles you jump in the early days will drop you.

- You feel the fear and you keep going. You don’t defend the ‘as is’; you focus on the ‘should or could be’

7. ELEVATING THE VISION: DOING IT ALL AGAIN IN 2018 – DID WE HAVE THE COURAGE, COULD WE STAY THE COURSE, WAS THE PURPOSE ENOUGH?

In many ways, accepting the feedback, changing the program, looking at ourselves was the ultimate test of the purpose and our commitment. For me personally, as the dreamer and CEO, the social entrepreneur, leadership expert and the cause of many of the challenges we faced, looking into the mirror, and responding to the feedback, was more revealing than the preceding couple of years of hard labour.

Once I had overcome my fear of not being approved of, not being worthy, not being loved by the people I was dedicating myself to I recognised that this would be the journey of my life time. Though I felt it at times, this was not a criticism of me personally. This was not a negative criticism of an important project put on by passionate people to help influence the global narrative of leadership. It was a monumental gift.

IF we could listen, IF we could change, IF we could grow, then we would be part of a global initiative that mattered. We would matter. The women we were helping would matter.

So, we swallowed our own medicine. As leaders, all of us went through the trial by fire, the Apotheosis that Joseph Campbell talks about in The Hero’s, and we survived.

Although the second Homeward Bound was entered into with trepidation, knowing that if it didn’t work, we would all have downed tools, thanked each other for the adventure and walked away, it did work. We didn’t give in. Instead, we came together and delivered a stunning experience (with slight changes to the faculty including being joined by several alumni). So much so, all the participants signed a shared email to HB1 to acknowledge the changes they observed, including the commitment of the faculty to respond to the feedback from the first cohort and the real improvements for the better that had eventuated from that.

We were overjoyed. The hard work and courage had paid off. Now it was time to settle into the ten-year ambition and embrace the ongoing learning.,

It was also the beginning of a true global collaboration, a very different way of leading that incorporated institutionalised feedback on what we were doing and how we were doing it.

Advice

As Churchill famously said, “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Homeward Bound has gone on to garner recognition globally for its contribution and for radically elevating the visibility of women leading with a STEMM background. As of end January 2020, 1.3 billion people have heard about the initiative, well known in countries as far flung as Pakistan, Chile, Spain and Canada. It has ripple projects in France and Kenya. To date, 48 nationalities and 36 sciences have been involved.

Today, the organisation has full not for profit status, a governing board (and some 8 board sub committees, a significant broad faculty, and each year a refreshed on-ship faculty. We have an ‘elders’ program and are attracting high profile women in their sixties from around the world to join each year as mentors to the women. We have extensive alumni collaborations, literally thousands of public appearances or speeches given by the women. We have TED talks, promotions and increasing visibility in places that matter.

As a seasoned CEO, I look on this as the opportunity of a lifetime, and I will probably spend the rest of my days digesting the lessons and implications to the practice of leadership globally.

If we are to secure a sustainable future for our children and we are the leaders to affect the change needed, this is the decade for change.

It is neither fair nor appropriate to leave the heavy lifting to the young women and men of the world.

It is for all of us to stand up and lead for the greater good, future proofing the road ahead for all.