Using the power that comes with leadership ethically and effectively is a make-or-break competency, and one that’s largely overlooked, according to an expert coach.

Positions of power have “a set of behavioural competencies that need to be mastered”, says leadership specialist Julie Diamond, the founder of Diamond Leadership and the author of Power: A User’s Guide.

“Power shapes, it normalises, it sends the message: ‘this is okay’. And it’s not just what a leader does, it’s what they don’t do.”

This includes, for example, when a leader doesn’t call somebody out, or name a behaviour as inappropriate, or follow up with people, or hold them accountable.

“When you don’t intervene; when you let someone take over the meeting; when you don’t raise a difficult topic… that’s conflict aversion. That’s where, for me, leadership use of power shapes culture,” Diamond says, yet power is not often referred to as a competency, and some leaders have a “power problem” without realising it.

When a person becomes a leader, they might not stop to think about what it means to occupy a role of power and to use that power well – not just the “positional power”, but power that comes from authority, expertise, seniority, relationships and networks.

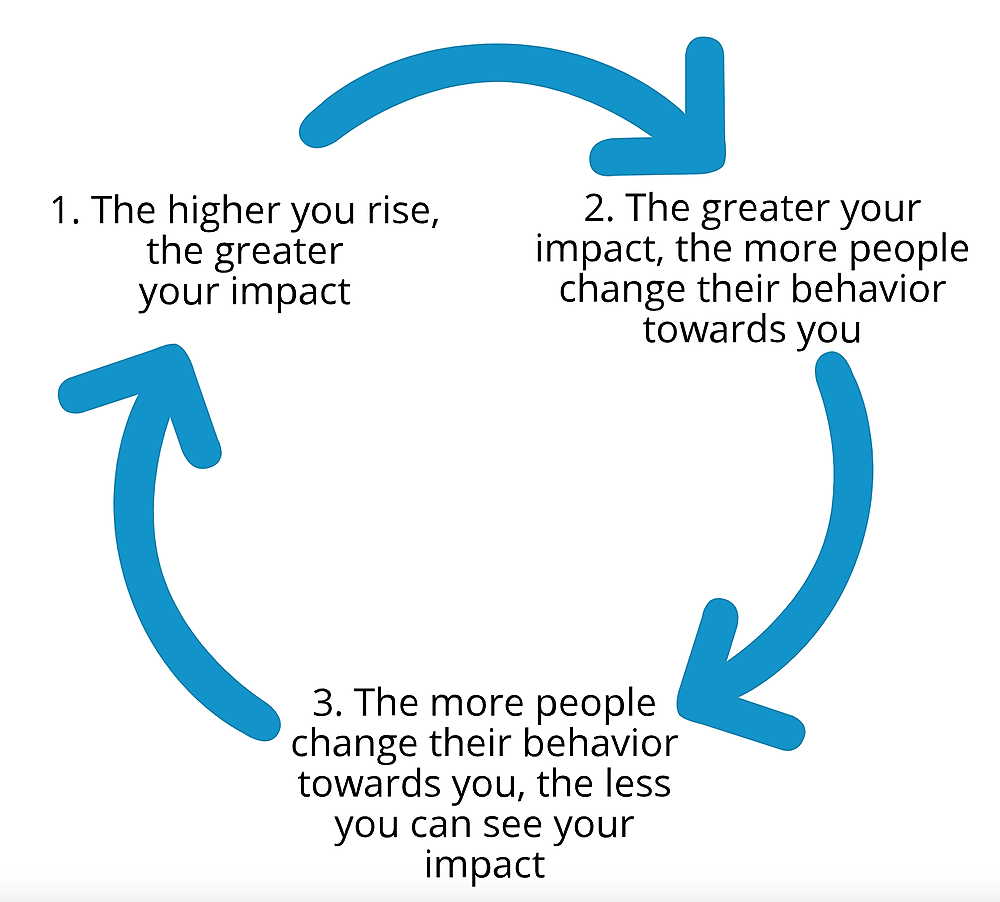

Whether they welcome it or shy away from it, and however “nice” they are, documented research shows that “power changes you cognitively [and] emotionally; it changes how you think, how you feel, how you perceive, but it also changes the people around you”, Diamond says.

“It changes how people relate to you, and so you start to get this very skewed perspective.” It’s why studies show that when leaders are asked how the organisation’s culture is doing, in many cases most will say “Great!”, while the same proportion of employees report the opposite.

Dimensions of power

The Diamond Power Index (DPI) is a developmental tool that Diamond created, which has been taken by more than 25,000 leaders across the globe.

Based on five years of research into leaders’ use of power – both effective and ineffective, healthy and dysfunctional – it considers seven dimensions, the first of which is approachability. This relates to a leader’s self-awareness around how intimidating or approachable they are.

“This is what’s commonly thought of as psychological safety. It’s like: you are easy to approach, you foster conversation in your teams. People can open up, they can ask questions, you model humility, you ask questions, so it’s very safe to approach you,” Diamond says.

They’re also self-regulated, as opposed to emotionally unpredictable. “It also means that you’re available – literally available. You’re not scattered and changing your meetings all the time and never answering your emails, you really are available.”

The next competency, which is also in the self-awareness domain, is about being respectful. “You don’t behave inappropriately… This is the dimension that captures all of those really unfortunate behaviours like sexual harassment and offensive, rude, bullying behaviour, and it means that you monitor yourself,” Diamond says.

These leaders understand and attend to what’s appropriate, they’re context savvy, and they have a feedback loop, she explains. For example, “I say something, I see how it lands, and then I monitor myself based on how it lands”.

Another domain is “other awareness”, or “working with others”, and whether a leader is seeking to develop and empower others. It relates to the idea that 50% of a leader’s job is to deliver results, and the other 50% is to develop others to deliver those results. “And so you seek to understand the developmental needs of the people you’re leading. You coach, you give accurate feedback, you check in with people, you are clear.”

Leaders can, intentionally or unintentionally, disempower people if they don’t provide clarity around a task and the outcome they’re looking for, Diamond notes. This can leave employees confused, and with a sense the goal posts keep changing.

Also in the domain of “other awareness” is conflict competence – a leader can be conflict competent or conflict averse, or somewhere in between.

It’s important for leaders to realise that underusing power is as big a misuse of power as overusing it, Diamond says.

“When you don’t intervene; when you let someone take over the meeting; when you don’t raise a difficult topic, you don’t give negative feedback, you don’t hold people accountable, you’re not willing to call something out, you’re not willing to raise a difficult topic – that’s conflict aversion.”

Leaders need to be able to use their power “and not try to be friends and minimise your authority because you want to be liked or you’re afraid”, she notes.

A third domain is role awareness.

“One of the really interesting things about power is that there’s this intangible role awareness that we need to become versed in; it’s the symbolic aspect of leadership,” Diamond says.

“We have to learn what it means to occupy a role and that means you can’t take things personally. It means that you have to understand your boundaries, it means that you can’t just be chummy and friendly and disclose information, it means that you’re modelling behaviours.”

Sometimes leaders feel torn between the demands of their role and being authentically themselves, but Diamond says they should expect a degree of restriction when it comes to the latter at work. Even if they resist this, others will impose it, because they’ll still see and treat their boss as a boss.

Related to role awareness is being fair, diplomatic, and judicious.

Being fair means “you’re not biased, you don’t play favourites, you understand that your time and your attention is a resource that has to be distributed equitably”, Diamond says.

Being diplomatic means having professional boundaries: “You don’t disclose, you don’t vent, you don’t talk negatively about the organisation [or] complain about your colleagues”.

Finally, being judicious involves being moderate. “You restrain yourself, you’re not indulgent, you put the needs of the organisation ahead of your self-interest. You understand that it’s not about you, it’s about the organisation. And so you don’t use your role for your own gain. You don’t put your agenda first and argue with your colleagues about who gets the budget and whatnot, but you’re asking, ‘What’s best? What’s best for the organisation?'”

Power skews leaders’ perceptions

“When people change their behaviour towards you, you really don’t get an accurate perception of how well you’re doing,” Diamond says.

“People will soften or massage their message – they don’t want to tell you the bad news, or they just curry favour, or they’re just sceptical and protective, and that’s a hard-wired response,” she explains.

“Power gets in the way because we’re a social species,” she adds. “We’re hard wired to respond to rank and power in self-protective ways. That puts leaders at a great disadvantage.”

For this reason, Diamond says leadership development should focus on helping leaders “make the impact that they want to make, not the one that’s unintended, that they don’t even realise they’re making”.

This article first appeared in HR Daily.

At Dattner Group, we integrate the Diamond Power Index (DPI) into our leadership and culture programs to help leaders understand and use power effectively. If you’d like to explore how this diagnostic could transform leadership in your organisation, we’d love to talk.